Okay, we need to talk :)

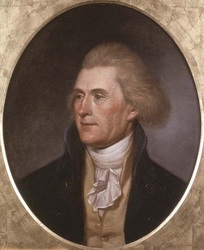

I am doing my thesis research on an American painter named Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) and when I tell people this I get some blank stares. He is not one of the most well-known artists out there so let me introduce you to him. It is actually surprising that many people can barely name any early American artists at all. We can all name some founding fathers and scientific inventors from this time, but rarely any artists. That is a shame because some of these artist did a great deal for the American Revolution. How do you know what Benjamin Franklin or Thomas Jefferson look like? Paintings, of course! These artists recorded history makers and the history they made at a time when television and photography did not exist. The most well-known early American artists are John Copley, Benjamin West, and Gilbert Stuart. Interestingly though, these artists were only born in the colonies and spent much or all of their adult and professional lives in England. This was where the great art education could be found. Charles Willson Peale, on the other hand, spent only 2 years in England to improve his skills under the tutelage of Benjamin West. He was an outspoken champion for the American cause from the moment of the infamous Stamp Act. He was in England at the time and was said to refuse to take his hat off as the King rode by. He made propaganda portraits (even while he was still in London) to promote the cause of liberty for the colonies. I may explain some of these portraits in a later blog, but for now just an overview of Peale and his contributions.

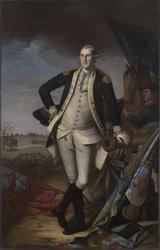

He came back the colonies and enlisted in the militia. His militia company was called to join Washington and his troops in the fall of 1776. He also endured the long, brutal winter at Valley Forge. Even in the militia he did not completely neglect his art. He brought his miniature paintings set and completed many miniatures of generals that we would have no other visual record. He also recorded the re-crossing of the Delaware (a much more accurate depiction than the famous, dramatic one you have probably all seen by Leutze).

He painted numerous portraits of revolutionary characters including George Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, Lafayette etc. I may also do a blog entry on some of these images later. He painted at least seven portraits of Washington alone. He painted nineteen copies of one of these Washington portraits!!

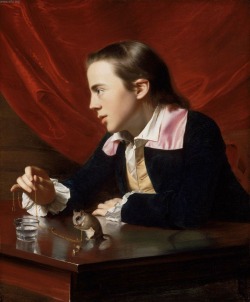

He also created numerous portraits for wealthy merchants throughout the Northeast. He is wonderful at capturing sweet moments in his portraits, especially in images of mother's and children and family portraits in general.

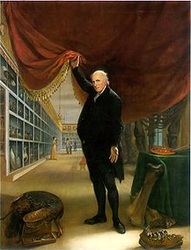

He also created America's first natural history museum. He collected most of his own specimens and mastered the art of taxidermy to preserve them. He created environments for the animals. It seems like quite an impressive achievement from what I read, especially for the early 1800s. It was a successful venture for quite awhile and eventually (after Peale's death) sold to P.T. Barnum who would later use some of it to create his circus attraction. YES, Charles Willson Peale helped create some of the attractions in the first circus!

Peale had sixteen children!!! many of these children became artists as well. Perhaps this is because he named most of them after famous artists (and some scientists) Examples: Rembrandt Peale, Rubens Peale, Raphealle Peale, Angelica Kaufman Peale, Titian Ramsay Peale and so on.

:) I have come to really enjoy this fascinating man, a Renaissance man from the birth of our nation.

Now for some pictures:

I am doing my thesis research on an American painter named Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) and when I tell people this I get some blank stares. He is not one of the most well-known artists out there so let me introduce you to him. It is actually surprising that many people can barely name any early American artists at all. We can all name some founding fathers and scientific inventors from this time, but rarely any artists. That is a shame because some of these artist did a great deal for the American Revolution. How do you know what Benjamin Franklin or Thomas Jefferson look like? Paintings, of course! These artists recorded history makers and the history they made at a time when television and photography did not exist. The most well-known early American artists are John Copley, Benjamin West, and Gilbert Stuart. Interestingly though, these artists were only born in the colonies and spent much or all of their adult and professional lives in England. This was where the great art education could be found. Charles Willson Peale, on the other hand, spent only 2 years in England to improve his skills under the tutelage of Benjamin West. He was an outspoken champion for the American cause from the moment of the infamous Stamp Act. He was in England at the time and was said to refuse to take his hat off as the King rode by. He made propaganda portraits (even while he was still in London) to promote the cause of liberty for the colonies. I may explain some of these portraits in a later blog, but for now just an overview of Peale and his contributions.

He came back the colonies and enlisted in the militia. His militia company was called to join Washington and his troops in the fall of 1776. He also endured the long, brutal winter at Valley Forge. Even in the militia he did not completely neglect his art. He brought his miniature paintings set and completed many miniatures of generals that we would have no other visual record. He also recorded the re-crossing of the Delaware (a much more accurate depiction than the famous, dramatic one you have probably all seen by Leutze).

He painted numerous portraits of revolutionary characters including George Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, Lafayette etc. I may also do a blog entry on some of these images later. He painted at least seven portraits of Washington alone. He painted nineteen copies of one of these Washington portraits!!

He also created numerous portraits for wealthy merchants throughout the Northeast. He is wonderful at capturing sweet moments in his portraits, especially in images of mother's and children and family portraits in general.

He also created America's first natural history museum. He collected most of his own specimens and mastered the art of taxidermy to preserve them. He created environments for the animals. It seems like quite an impressive achievement from what I read, especially for the early 1800s. It was a successful venture for quite awhile and eventually (after Peale's death) sold to P.T. Barnum who would later use some of it to create his circus attraction. YES, Charles Willson Peale helped create some of the attractions in the first circus!

Peale had sixteen children!!! many of these children became artists as well. Perhaps this is because he named most of them after famous artists (and some scientists) Examples: Rembrandt Peale, Rubens Peale, Raphealle Peale, Angelica Kaufman Peale, Titian Ramsay Peale and so on.

:) I have come to really enjoy this fascinating man, a Renaissance man from the birth of our nation.

Now for some pictures:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed